Sometimes it feels like robots only exist to be abused, you know? We love them and the window they provide on the human condition, but science fiction is usually pretty mean to them overall. It loves to torment robots (and when we say “robots” we’re really talking about any form of android or A.I. or sentient toaster or what-have-you) with the constant threat of obsolescence or deactivation or destruction. And some of these deaths are just plain gratuitous, leaving us betrayed, bewildered, and otherwise bereaved.

Here are the worst of them.

Data, Star Trek: Nemesis

Type of “Robot”: Android

Why Death Was Gratuitous: Look, Nemesis was supposed to be the big bow-out for the Next Gen cast, but it just didn’t work that well. The plot was fuzzy, the villain weirdly contrived, and nothing about the film seemed to truly embody the tone or themes that Next Gen tackled. But perhaps the greatest offense of all was that, in the desire to make the final film feel like an epic sendoff, Data rescued Picard from Shinzon’s ship before sacrificing himself to keep his friends safe. This is already upsetting enough, seeing as the script seems to use Data’s death to make the audience “feel” how important the events of the film are, even when they aren’t well-executed. But then there’s the problem of B-4 to contend with as well.

Nemesis introduces an earlier version of Data named B-4 (GET IT) into the mix, a less advanced model who has none of Data’s experiences. At the end of the film, Picard finds out that Data downloaded engrams of his neural net into B-4 before making his sacrifice play. So Data kinda dies but also doesn’t. B-4 is probably never going to be Data, but he’s there-ish. Which just makes Data’s entire arc in the film seem like a waste and an insult. Either go for it, or don’t. And then please attach it to a better film. —Emmet Asher-Perrin

The Stray, Westworld

Type of “Robot”: Host, or android

Why Death Was Gratuitous: Really, every death on Westworld stretches the limits of palatability, and the one you choose is probably a better litmus test than most. While I feel for poor Teddy’s 5,000-plus deaths at the hands of Westworld’s trigger-happy clients, what stuck with me was the rare case of host self-harm early in season 1. When Elsie and Stubbs discover a random host who has strayed from his normal narrative loop, he demonstrates that while something is wonky in his circuitry, his programming—do not kill humans—is intact.

Stubbs tries to decapitate him so that they can take his brain back to the lab for analysis, so of course the host’s survival instinct kicks in and he begins to fight them off. But whereas a human would perhaps try to behead Stubbs in retaliation, this host makes the necessary calculation for the correct outcome: He picks up a boulder and bashes in his own head—a grisly sequence that goes on much longer than it needs to. (I should add that I have not yet caught up on season 2, so there could likely be a much more gratuitous death waiting for me, oh boy.) —Natalie Zutter

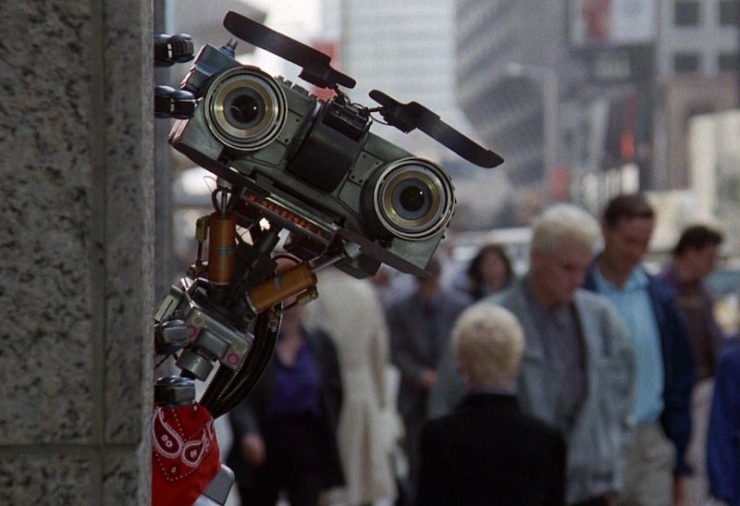

Johnny 5, Short Circuit and Short Circuit 2

Type of “Robot”: Alive, preferably

Why Death Was Gratuitous: Short Circuit and its sequel really commit to robot agony. Entire scenes are devoted to Johnny 5 (whose sentience, please remember, is either an accident or the act of a confusing and unknowable God—not even the film’s creators know for sure) pleading to all of his human captors/friends “NO DISASSEMBLE!” It’s a cri de coeur that more often than not goes unheeded as the bastard meat sacks pummel him and attempt to strip him for parts. He dies twice in the first film. The first death is brief: he’s simply powered down, and somehow regains enough consciousness to escape. The second time he and his human friends Ben and Stephanie are under attack by an evil robotic lab, and he appears to sacrifice himself to keep them safe. It’s only revealed that Number 5 is Alive! at the very end of the film, after long moments of believing DISASSEMBLY had come for the plucky robot at last.

But that’s nothing compared to the sequel. Would-be thieves beat Johnny to a pulp as he screams, “No kill! Am alive! Am alive!” and he later has to foil a bank heist while barely conscious—it’s only the raucous energy of Bonnie Tyler’s “I Need a Hero” that keeps him going. Johnny finally loses power until Fisher Stevens’ Ben Jahveri, a walking hatecrime human friend, keeps him alive with a defibrillator. —Leah Schnelbach

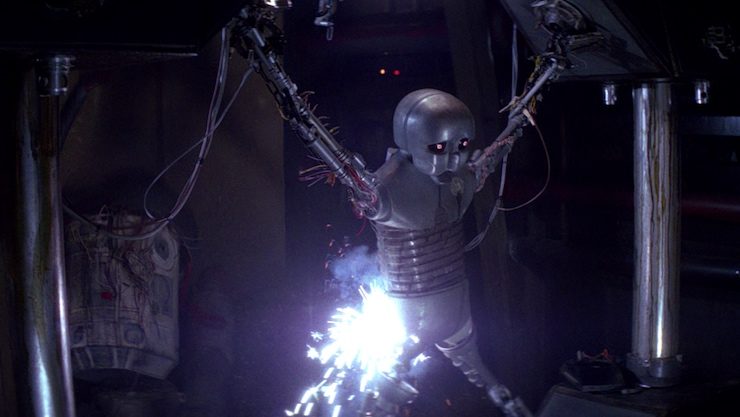

Battle Droids, Star Wars: The Clone Wars

Type of “Robot”: Droids

Why Death Was Gratuitous: In the Clone Wars, the Separatist army is made up almost entirely of battle droids. They are clearly designed to overwhelm the enemy through sheer numbers, as the average battle droid is little more than a skeleton that can hold a blaster and follow orders. In Episode II, this doesn’t seem like much of an issue. By the time you get to The Clone Wars series, things get a little more iffy.

It turns out that the battle droids are keenly aware of their canon fodder status. They show clear dread when Jedi show up during their campaigns, knowing that their chances of surviving have been cut down to nothing once lightsabers and the Force are involved. They get excited when they make it through—only to get cut down at the last minute, often. It’s a reminder of how awful the Star Wars universe is to droids in general, and also a very pointed reminder that there’s no such thing as a “disposable” army. —Emily

Megaweapon, Mystery Science Theater 3000, Experiment 501: “The Warrior of the Lost World”

Type of “Robot”: Sentient Tank/Actor

Why Death Was Gratuitous: Megaweapon’s death isn’t actually that gratuitous. By this list’s standards, it’s fairly quick. But I felt it deserved a space here because in the MST3K episode “Warrior of the Lost World” we’re afforded the rare opportunity of watching robots respond to another robot’s death. Since the human characters in Warrior are uniformly detestable, and since the only other robotic sentience is the main character’s jive-talking motorcycle (who’s somehow worse than all the humans combined), Joel and the Bots start actively rooting for Megaweapon to murder everyone else and take over the film. Alas, it is not to be.

When Megaweapon gets blown up, the Bots are inconsolable. “Megaweapon was cooler than all you guys!” Crow sobs at the screen. After the film, Joel tells the Bots that Megaweapon’s fine, of course—he’s just an actor! Joel found his phone number and as a special surprise he arranged a call for Tom and Crow. He’s staying with his sister in Tampa, and they dish on Killdozer (a diva, apparently) as Megaweapon’s nieces and nephews scream in the background. Megaweapon tells them that if they ever come back to Earth, he’ll be in Tampa for a while, but then he’s headed to Indianapolis for about a month and they should look him up. —Leah

Gina Inviere, Battlestar Galactica

Type of “Robot”: Cylon, or android

Why Death Was Gratuitous: On BSG, death was often a mercy for Cylons, or even a convenient trick; as long as a Resurrection Ship was in orbit nearby, they could peace out of a dire situation and live to fight humans another day. But by the time that Gina, a Number Six Cylon, is begging Gaius Baltar to kill her on multiple occasions, it’s just heartbreaking. Yes, she’s a Cylon spy, without the plausible deniability of the other sleeper agents; she infiltrates the Pegasus and earns the trust of the other officers as well as the Admiral, her lover Helena Cain. Yes, she plots to sabotage the ship and accepts the responsibility of killing however many humans she has to to carry out her mission. Except, that is, for Cain, for whom she seems to have developed genuine feelings.

Not only is Cain unwilling to consider these human-like behaviors, but she reduces Gina to a “thing”—a thing that she allows one of her officers to degrade, fear, and shame through torture and gang rape. Rather than extract information as intended, they only force Gina into a catatonic state. While a rescue from Galactica provides her a second chance at life, what she truly wants is to not live in any form—not resurrected, not as another Number Six. Though she begs for death, it is only after she is forced to demand “justice” by killing Cain, and a brief stint pretending to demand peace for humans and Cylons, that Baltar gifts her a nuclear warhead that she uses to blow up the ship Cloud Nine and herself. She doesn’t even want to continue her line’s work, yet she still has to beg for the end of her life. —Natalie

David, A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Type of “Robot”: Mecha, an advanced humanoid robot

Why Death Was Gratuitous: This movie is clearly meant to be a rumination on love and ownership and what it means to be real to yourself and others, a kind of Velveteen Rabbit for robots. And it is devastating for a number of reasons, the primary one being that David’s first death isn’t really a death at all—it is the act of being abandoned by a woman who was supposed to be a mother to him, Monica Swinton. This sends David on quest to become human, thinking that once he is no longer a mecha, Monica will be able to love him. He witnesses a great deal of mecha death and abuse at the hands of humans, and eventually his journey to find the “Blue Fairy” (of Pinocchio, bestower of human status) leads him to a submerged Coney Island where he finds a fairy statue and repeatedly asks her to become human until he runs out of power.

He is woken 2000 years later by an evolved version of his species, long after humans have died out. And even then, he chooses to spend his time with a short-lived clone of his mother so he can be in her presence one last time. Everything about this is horrible. David having an imprinting protocol that allows him to become this attached to a woman who is using him as a replacement for her ill son is already horrific enough, leading to David’s inability to think of anything but becoming human for her. He dies asking a freaking fairy statue to make him a real boy until withers away, this is the worst thing. The worst. Ever. —Emily

C.H.O.M.P.S., C.H.O.M.P.S.

Type of “Robot”: Robotic Doggo

Why Death Was Gratuitous: This is a film that was intended for elementary school kids, but which also featured two protracted scenes in which a very lifelike robot dog is blown to pieces. (See above.) C.H.O.M.P.S. takes a simple problem, and gives it the most late-’70s solution imaginable. You want home security, right? How about if, instead of an alarm, you get a robotic dog who can emit a variety of terrifying sounds, and whose eyes glow red whenever your home is threatened? But he’s not like, a Rottweiler, just a knock-off Benji. Also, how about if the plot of the film hinges on the idea that multiple absurdly powerful, family-owned home security companies are vying for control of a single small town? And how about if an engineer is dating the daughter of the CEO of one such company, and invents a robot dog to impress him, but then the other company spends the whole movie trying to steal his plans?

What we get is a masterfully gratuitous robot death. First the movie fakes us out, making us think that C.H.O.M.P.S. has been blown up in a weird training exercise (corpse pictured above). But he recovers from that, only for the rival company to plant a bomb in his engineer’s office, so then he gets blown up AGAIN (even worse) and precious moments of screen time unspool with C.H.O.M.P.S. seemingly on his way to Silicon Heaven…until his eyes starts to glow with life suddenly because he has soul? Or something? Anyway, the movie ends with more C.H.O.M.P.S. models being put into production, but given that this was a children’s film that treated its audience to not one, but two protracted explosion-deaths, it earned its spot on this list. —Leah

Buffybot & April, Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Type of “Robot”: Sex Bots

Why Deaths Were Gratuitous: Though initially created to be Spike’s sex toy, the Buffybot eventually became a part of the Scooby gang, acting first as a decoy against the god Glory and then standing in for the real Slayer following her death. Patrolling Sunnydale at night and acting as Dawn’s guardian during the day, Buffybot kept the spirit of Buffy alive and prevented both her domestic and supernatural situations from devolving into too much chaos. And despite her penchant for taking things too literally or saying something odd that would jolt everyone out of the illusion, she still represented Buffy in some form and helped the Scoobies to bridge the gap between Buffy’s sacrifice and her resurrection.

Which is why she deserved better than to be drawn and quartered by a vampire biker gang who discovered her true nature and decided to have some fun with seeing just how invincible the Buffybot was. And even after they’ve pulled her limb from limb and all that’s left is her short-circuiting torso, she can still look at Dawn and pass on one final message: That the real Buffy is alive.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7WLC4NU1Pqc

But before Buffybot, there was April: another girl created by Warren out of fantasy and programmed solely for the purpose of loving him. But that’s the problem with programming—it gets predictable. And when he gets bored, he doesn’t do the honorable thing and shut her down; he runs away and hopes she doesn’t find him. He should be impressed at how tenacious he designed her, as she strides through parties and dorms searching for her one true love, throwing other men out of the way and threatening his new, flesh-and-blood girlfriend. Until, that is, she begins to power down.

April dies sitting on a swing with a sympathetic Buffy, unironically spouting aphorisms. It’s not even that it’s unironic, it’s that she still believes that Warren is coming back for her, that this slow darkening of her vision is another test in her quest to be the perfect girlfriend. Things will be better, she tells the Slayer, because “things are always darkest before—” Poor girl doesn’t even get to finish. —Natalie

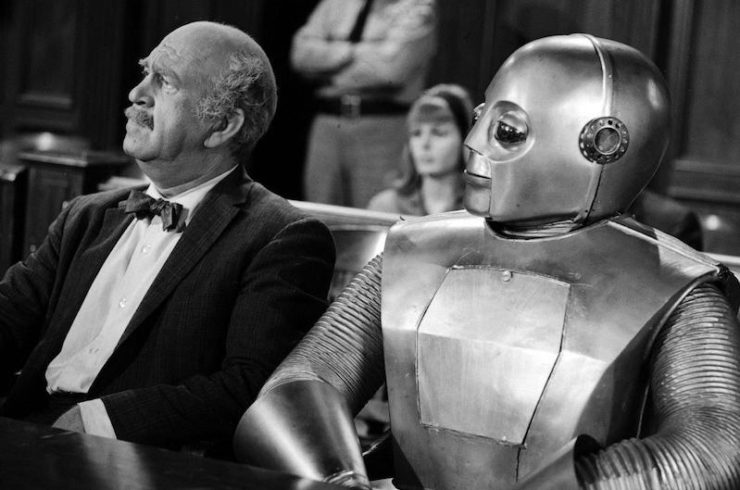

Adam Link, The Outer Limits, “I, Robot”

Type of “Robot”: Robot

Why Death Was Gratuitous: This episode is so heartbreaking that it was filmed for both the original Outer Limits and the ’90s revival. (Both of these episode feature Leonard Nimoy, albeit in different roles, and the central character was actually conceived in a series of short stories written by Otto Binder between 1939-1942.) Adam, a robot created by Doctor Link, is accused of killing his creator. The episodes are different in their execution; the 1964 version puts Adam on trial for the murder, while the 1995 version has Adam brought before a judge to determine if he has the right to be tried as a person at all, rather than disassembled.

Both versions make it clear that Adam is ultimately not to blame for the death of his creator, but that very few believe his innocence. As he is walked from the courthouse, a victim (in one version a child, in the other his prosecuting attorney) stands in the street about to be hit by a car—Adam throws them out of the way and ultimately sacrifices himself to save another. We go through all this questioning of Adam’s innocence, of his ability to murder, of his status as a sentient being, only to have him die right in front of us. I will be billing the show for the therapy needed after watching this hour of television. —Emily

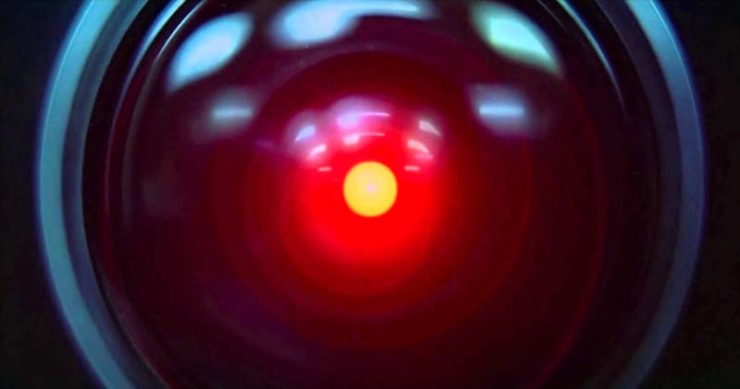

HAL 9000, 2001: A Space Odyssey

Type of “Robot”: Old School Desktop

Why Death Was Gratuitous: HAL’s death may have been the inspiration for this list. It’s horrifically drawn out and graphic in a particular way, but rather than being the culmination of a simple “human vs. technology” plot, it pulls all the film’s musings on the nature of consciousness and evolution together into one heartbreaking scene, while also honoring the history of computer science. HAL witnesses the astronauts saying they’re going to disconnect him. HAL, in true “NO DISASSEMBLE!” spirit, chucks a bunch of the astronauts into space. The one who’s left, Dave Bowman, manages to unplug HAL. But what’s great here is that there are a lot of plugs, it takes a long time, and HAL knows it’s happening.

Wait, maybe not great. Horrific. Yeah, that’s closer.

Anywhere, here’s “Daisy Bell.” —Leah

JARVIS, Avengers: Age of Ultron

Type of “Robot”: Artificial Intelligence

Why Death Was Gratuitous: JARVIS (acronym for Just A Really Very Intelligent System, which is basically the greatest thing ever) is Tony Stark’s butler A.I., modeled after Edwin Jarvis, who was his father’s real-life butler and an important guardian figure in Tony’s childhood. JARVIS the A.I. is clearly in part a memorial to this man, as well as a sort of precursor to fully sentient artificial life. He and Tony Stark are so interwoven that they have a shorthand between one another; Tony’s keyboards contain not letters, but symbols that are part of a personal language the two have developed, and JARVIS can anticipate what Tony needs in the Iron Man suits often before he asks for it.

But then Tony and Bruce Banner accidentally create Ultron, who seemingly kills JARVIS so that he can break out and run rampant. It later turns out that JARVIS survived and has been protecting certain networks from Ultron so he can’t get his hands on incredibly dangerous codes and weaponry. In order to help fight Ultron, Tony, Bruce, and Thor end up combining various technologies with JARVIS, some lightning, and the Mind Stone to create a completely new entity: Vision. And while Vision has been extremely useful to the Avengers, and Tony now has another assistant in FRIDAY, it’s just so damned depressing that we had to lose JARVIS to get there. He was truly special, and a testament to the life of the man who he was named for. Also, the first time that Ultron seems to snuff out JARVIS is traumatizing. —Emily

Originally published in May 2018

Yul Brenner in the original Westword

I’m not convinced ‘gratuitous’ is the right word for many of these deaths.

Some were necessary even in the story’s own context (HAL, Gina) and many were necessary in the context of the author’s vision. They may have been sad, or cruel – but they don’t seem gratuitous (unnecessary, uncalled for) to me.

I always thought the B-4 business in Nemesis was beyond silly. As a computer, Data would have made regular backups of his core functions and memories, most likely a continuous process running in the background and streamed to an isolated server. Getting Data “back” would have been merely an exercise in “C:/run data.exe” and press ENTER.

I mentioned this the previous time this article was posted:

The Interrodroids from “The Middleman” TV series. They’re basically in the show to be destroyed humorously, then replaced by an identical interrodroid.

Interrodroid Deaths:

Interrodroid 3000: smashed by Wendy Watson during her interrogation training

Interrodroid 4000: beheaded by replacement-Ida as she emerged from her box

Interrodroid 5000: blown up by an alien-boobytrapped Voyager 2

Interrodroid 6000: dismantled to use as a disguise for Wendy Watson

Interrodroid 7000: disintegrated by Ida because Ida couldn’t tell which was Wendy in disguise

And all of that was in just 12 episodes.

RIP (repeatedly), Interrodroid.

For some reason, the Battle Droids in Star Wars are programmed for fear of pain and death, and to also loudly vocalize that fear. The scene that sticks out to me is on the bridge of the Separatist cruiser in the opening of Revenge. It’s some Battle Droid technician trying to run away from Obi-Wan before he cuts it in half. It’s such a weird thing to do (I get why: killing people by cutting them in half a lot gets you an R) but it makes sense. No one wants to be cut in half by a slave knight with a laser sword.

@5

Why would you even program battle droids to fear pain or death? It seems like a waste of programming to give a battle droid all but the basic “march in straight lines, shoot stuff” instructions.

“I’m not convinced ‘gratuitous’ is the right word for many of these deaths.”

I suspect that either the author thinks gratuitous just means “particularly upsetting” or knows what it means but thinks that it is never necessary for a story to be upsetting; that, in fact, all cases of fictional violence (and all fictional nudity, bad behaviour and naughty words) is gratuitous (which is an arguable position though not one that I agree with).

HAL’s death is obviously not gratuitous. If HAL survives to reach Europa the story is completely different.

“Why would you even program battle droids to fear pain or death?”

You can’t be a good soldier if you don’t fear pain and death. Soldiers need to keep themselves alive so they can carry out their mission.

@6 I think it is indicative of the Trade Federation and Separatist leadership styles, done on the cheap. They’ve clearly taken some pre-existing off the shelf personality unit programming (form a protocol droid most likely) and done the bare minimum adjustment to make them function as soldiers rather than spend the time and money on RnD to come up with something specific to the task. Alas, even in a Galaxy Far Far Away capitalism is still broken.

@8

Don’t need to program in pain and fear. Just program in a risk/reward algorithm along with the mission orders. Something like “low risk = maximum conservation of supplies and resources” or “high risk = expend all necessary efforts to complete the mission”.

Fear of failure is more important than fear of death or pain. Professional armies since the Persians (at least, and that’s only talking the pre Western Roman collapse Mediterranean world) have been trying to convince their soldiers that death isn’t that big a deal. Fear of death means soldiers are less willing to take risks that would imperil physical safety, especially if that fear is paramount. It’s why suicidal last stands or desperate forlorn hopes are near universally venerated: they’re the right move.

And fear of pain and death doesn’t make sense in droids here. While Star Wars droids are mind shackled to obey, that should be an advantage. Injuring a clone trooper is just as good as killing , because it drains resources from the Republic (though I imagine clone trooper hospitals are probably just big macerators for damaged clones). Wounding or killing a Jedi would always be worth attempting from the Separatist perspective.

What about the looking of the Android in the Alien movie. Those were gratuitous.

Don’t forget Teddy from AI. He’s a loyal friend of David. Even 2000 years later.

Bishop in Aliens. Terminator 2. All of the “skin jobs” in Blade Runner. None of these are truly gratuitous but they fit the definition of the word for this story.

One of at least two reasons not to see THE ICE PIRATES is its staggeringly cruel gratuitous robot deaths.

“Don’t need to program in pain and fear. Just program in a risk/reward algorithm along with the mission orders.”

…what else do you think pain and fear are, if not a programmed-in risk/reward algorithm?

ajay @@@@@ 7:

I suspect that either the author thinks gratuitous just means “particularly upsetting”

Yeah, I think you’ve pinpointed the problem — except it’s not a single writer, it’s all four of them (assuming that “Stuffy the Robot” is not one of the other three).

Statements like “Really, every death on Westworld stretches the limits of palatability” or “it’s just heartbreaking” or “Everything about this is horrible” or “This episode is so heartbreaking” or “I will be billing the show for the therapy needed after watching this hour of television” or “it’s just so damned depressing” all contribute to the idea that the writers think “gratuitous” means “really sad and upsetting” (or, well, “heartbreaking”, which seems to be everyone’s favorite synonym).

HAL’s death is obviously not gratuitous. If HAL survives to reach Europa the story is completely different.

Not only that: Leah Schnelbach’s description of it (correctly if ironically) points out that

(I would only add that by making HAL’s death poignant and emotional, the scene also highlights the ironic and problematic similarity between the AI and the rather emotionless, even soulless, human beings in the film.)

Taken together, that’s pretty much the polar opposite of “gratuitious”.

Responding to Ragnarredbeard –

The problem wasn’t the data in Data’s memory. It was the positronic neural net Dr. Soong invented that was able to store and process so much so quickly and so compactly. No one else in the (known) Federation had ever come close.

B-4, I’ll agree, was a silly and lame story crutch to answer that problem.